On Hopelessness.

There’s a never-ending heaviness to the world these days, though we all know on some level that it’s always been heavy. The only difference is that the heaviness is pervasive: every ping on our phones, every tab on our computer, every third post on a website we scroll by triggers our fight-or-flight response. The world is a mess, and the anxiety cannot be forgotten or ignored. To allow one’s mind to trail off and toy with levity is to dance hand in hand with the new horsemen of ignorance and apathy.

We remain plugged in, turned on but inoperative, our feelings of motivation and hope crushed in our chest like a black hole that’s collapsing our futures inwards. Writers and philosophers have been wrestling with this same weight for centuries. Everything we are witnessing, they witnessed too. The technology, mediums, causes, and intricacies of motives and methods have changed, but the trauma, stress, anxiety, hopelessness and sense of overwhelming helplessness has always been the same.

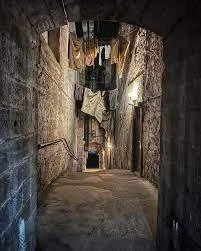

Last year, my partner and I visited Mary King's Close, one of the many underground streets in Edinburgh. That’s right, underground. Though it wasn’t originally underground, Mary King’s Close is a historic example of how the first skyscrapers were built. As the population of Edinburgh grew in the 16th century, people who weren’t able to expand outwards built upwards and created buildings which were up to 15 storeys high. Mary King’s Close is 12 storeys high, and now completely underground, as the city built on top of itself over time as buildings and defences rose higher. Why am I telling you this? Because of the plague. Over 600 people lived in Mary King’s close which, if you’ve ever visited with a couple of tour guides going around, you can only imagine how claustrophobic the space would have been. The poorest people lived on the lower levels, with the sewage, rats and faeces, and the wealthier lived at the top. During the bubonic plague of the 17th century, the close was forcibly sealed off from the rest of the city in a desperate attempt to quarantine and contain the relentless spread of the disease.

The people inside, cramped, were isolated, terrified, suffering and watching everyone around them die, and it’s believed the vast majority of the people living in the close did. As we stood in a tiny stone room in the dead of Scottish winter, I couldn’t even imagine the fear and hopelessness which suffocated this room hundreds of years ago. The suffering from that time is invisible now, flooded under centuries’ worth of what others would call even more tragic suffering. Now, that suffering is a ghost tour. A tourist attraction. It’s something other people enjoy, not in a sadistic way, but as part of a modern intellectual activity.

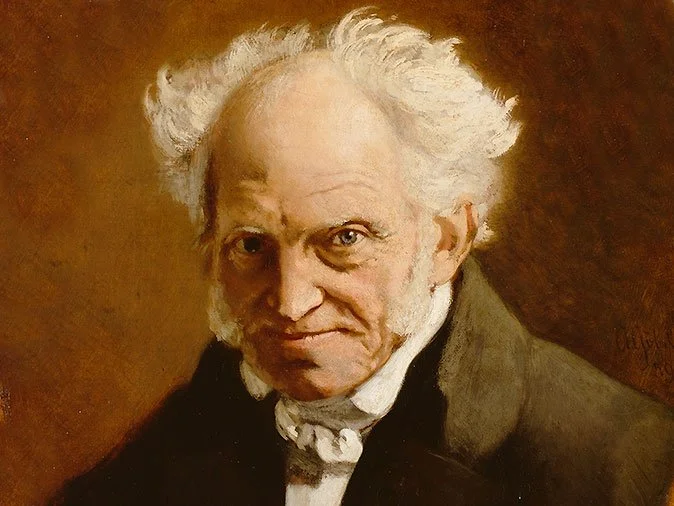

Is that the fate of all fear, and if so, are there ways for us to intellectualise our own anxieties in situ, or is that merely the privilege of future us? For Arthur Schopenhauer, life is unavoidably steeped in suffering. It is only by acknowledging that suffering lies at the heart of our existence that one can develop wisdom. Schopenhauer sounds terribly bleak on the surface, but it is remarkably uplifting (in a twisted sort of way). There is a time before you were born, and there will be a time after you die, and both of these realms are somewhat equal. You have no comprehension of either, and you are not able to suffer in either. Between these two periods of the universe is a blip: your life. In this life, there will be suffering, but suffering is a positive experience rather than a negative.

Positive, in this instance, does not equate to “good”, but rather “the presence of something”, and negative means “the absence of something.” Schopenhauer uses the example of a shoe pinching your foot: it is the presence of pain which has caused suffering. The rest of one’s body is fine, but the focus turns to the corner of our toe which hurts, and this pain consumes our present feelings. Suffering is a dominant force, and it demands all of our attention, and our brain magnifies it disproportionately, erasing all notions of where it is absent. When we feel happiness, we are usually engaging with something which negates our suffering: reading negates feelings of ignorance, coffee with friends negates our feelings of loneliness, engaging with a hobby negates our feelings of boredom.

Suffering is a very human reality, a daily reality, unless we find opportunities to negate the feeling in whatever ways we can. It’s quite an empowering philosophical outlook, one that encourages action to not only negate our own suffering, but the suffering of others. In this little blip of timeline in which we exist, we have the opportunity to respond to the very continuous, ever present concept that is suffering: it is inevitable. It is part of our daily experience, and our minds will choose to focus upon it. In our desperate desire to make all suffering end, we waste our brain’s opportunity to calculate ways in which we can negate.

It’s very easy to create suffering in this world, which is why so many people choose this way of life. It makes them feel productive, and in choosing to cause ourselves to suffer in our minds, we feel we too are productive members of society: self-aware, conscientious, morally righteous. But the suffering of this world happened before your life, and it will happen after your life too, and it would have happened if your life never did. If your blip in this timeline never occurred, the suffering would have continued. Suffering does not require more witnesses. It requires negaters.

Reader Reflection: When you feel hopeless, what words do you turn to?

📚 Further Reading on Hopelessness & Meaning

Albert Camus — The Myth of Sisyphus

Friedrich Nietzsche — The Gay Science (esp. §341, Eternal Recurrence)*

Arthur Schopenhauer – Essays and Aphorisms

Viktor Frankl – Man’s Search for Meaning

Rebecca Solnit – Hope in the Dark